By Christine Howie

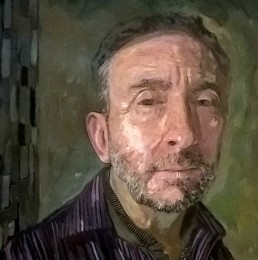

Artwork: Chris Kent

Christine Howie’s poignant, critical insight into the dissonance between body and mind when chronic pain makes identity hard to consolidate.

I’ve never not known pain. It’s the one thing I can always count on; my constant companion. I try not to let it get to me but some days that’s a difficult task. Some days the pain is everything.

I don’t remember much. I heard it all second hand; the things that happened to me. It’s a lot to process retrospectively, and I only understand this now through hypnotherapy and writing therapy. It’s been a long time coming and closure still awaits.

I was only two; there was a tumour. It was aggressive — not cancerous but precariously placed in the spinal cord. It deformed my tiny body, bending me this way and that. Things didn’t look good; I was baptised (just in case).

Then it was all gone, everyone was relieved and delighted. From what I’m told it was miraculous! I could still use my legs — even when they’d said a wheelchair or callipers would be the best possible outcomes — and there was no sign of major nerve damage. I used a toddler sized zimmer frame and learned to walk again — like the first time wasn’t enough.

As I grew my spine did what it wanted. I only became aware of it when I was around 8 or 9 years old. Until then, I was in the bliss of youthful ignorance. As it should be. The leg length discrepancy was the worst; I limped and hated myself for it; it felt shameful. I just wanted to walk like everyone else. My back was curved more on the inside than out so there was thankfully no hunch. That was all an adolescent needed. Life’s hard enough!

I was teased and I cried, but I built up resilience and resistance. Both of which have stayed with me; even now I sometimes distance myself from the people I love. Self-protection at its worst.

Today, I’m still battling with my body; still trying to accept it. I don’t like the limitations it’s placed on me; the many things I can’t do and the scars I bare. Like the one that runs the full length of my spine, or the slash across my torso where they removed a rib to graft my missing vertebrae. I look like a shark attack victim.

It took thirty years to convince anyone to give me the surgery, which I thought would make everything better. I would have spinal fusion, the rods and screws would save me. I’d be straight; my legs would measure up; it would all be a thing of the past. I wanted it so much I was prepared to lay on the table for fifteen hours while they literally tore me apart.

I underestimated how horrific recovery would be. I can only describe it like a trainwreck survivor who is then steamrolled over. I’ve never felt anything like it. The pain was so severe I was given ketamine. I had sympathy for my two-year-old self. Ironically, I had a nearly two year old son at the time, a dependant who I couldn’t lift or hold or care for during those first few months. I became a dependant myself. I could go from bed, to recliner to commode. My dignity was gone and this was hard to bare. It broke my heart and I struggled not to resent those that helped look after my son when it should’ve been me. I learned to mask the physical and emotional pain for his sake, I was a master at it, having many years of practice. I was just there in the chair.

The side effects and withdrawals from the meds were another battle I wasn’t aware I’d have to fight, I came to understand ‘cold turkey’ as I hallucinated and shivered through the night. I’d claw my skin as it itched until I drew blood. I was a mess; I questioned everything. At the time I wish I hadn’t gone through with it. How could I have done this to myself, my husband, son and family members? How selfish was I electing to have this surgery?

Even now I have doubts, nothing’s really changed all that much. It was more surgical prevention than a cure. I know the purpose was to avoid future implications and a complete fold over situation where my spine could likely collapse. I failed to realise that at the time though; I thought it would fix me. My expectations were too high.

I’m sure one day I’ll be thankful it happened but today is not that day. My spine is straight(er), my legs are still at odds with each other, my pelvis is tilted and a hip replacement imminent. I can’t paint my toes, do a shoe buckle or lace up. I struggle to play on the floor with my son, but I do it for short bursts. Sometimes, I feel like I’m making up for my absence.

The pain has never gotten better. In fact, it’s worse than ever. It doesn’t help that people think the surgery has taken it all away, cured the lifelong chronic pain and corrected everything. If only.

For now I simply keep on going but I’m exhausted physically and mentally. I battle with my body, I’m still at odds with it, I struggle to accept this body is mine, it’s not the one I wanted. I think of it as a separate entity, we are one but not. Despite all this, it carried and nursed a child who I’m watching grow into an amazing human being and for that I’ll be forever thankful.

As I get older I know I ought to be kinder to my body, it’s the only one I’ve got and we’ve been through a lot together. Hopefully soon we’ll reconcile our differences, make peace with what we did and embrace who we are.

Christine Howie

Christine lives with her husband and son (a wonderful and lively five year old) on the outskirts of Glasgow. After some time out to become ‘tinmum’ (titanium fused spine – Sia eat your heart out), she has been teaching Theology and Philosophy, volunteering for Pregnancy Sickness Support and writing whenever she can. At the end of 2017, Christine decided to make the leap creating a blog – tinmumblog.com writing about the minefield that is motherhood. She also tried where possible to help raise awareness of Hyperemesis Gravidarum (HG) – an illness she suffered throughout her pregnancy, which is still vastly misunderstood.

Chris Kent

Chris Kent is an artist, illustrator and woodworker who identities as non-binary. Chris lives in the Scottish Borders and sometimes works in Edinburgh for Edinburgh Museums and running workshops. Chris explores ideas of identity/uncertainty mainly by making art.