Josie Deacon

Photography by Josie Deacon

Passive as I live, little as I spoke, cold as I looked, when I thought of past days, I could feel. – Lucy Snowe, Villette by Charlotte Brontë

There are many books being published nowadays that feature mental health heavily as a theme, but did you know that Charlotte Brontë wrote a book about a young woman having a mental health crisis?

I want to talk about Brontë’s last novel, Villette.

The story follows Lucy Snowe, 20-something, no family or fortune, and suffering from some past trauma we never know of (presumably the death of her close family). In a spur of the moment decision, she travels to the fictional town of Villette and becomes an English teacher in a girls’ boarding school. She meets a cast of strange characters from Madame Beck, the owner of the school, to Mr Paul and Dr John, both men who catch the attention of Lucy.

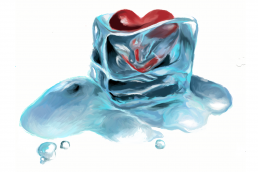

Lucy is quite clearly introverted, anxious, and suffering from depression. She is constantly fighting her own feelings, describing the negative thought patterns as “Reason” and her honest raw feelings as “Imagination”. At the end of Act One of the book, she spirals into a depression so terrible and lonely that she becomes physically unwell and faints on the snowy streets of Villette.

“The book is written in first person, and never have I read a narrator that says so little but reveals so much.”

The book is written in first person, and never have I read a narrator that says so little but reveals so much. I don’t mean that she is an unreliable narrator — she just does not wish to disclose to the reader her innermost thoughts, she doesn’t even want to disclose them to herself. She keeps her motivations to herself but from her actions and the way she views and describes her surroundings we learn so much.

The most startling thing about this Victorian novel is how clearly Lucy’s depression is caused by patriarchy. She denies herself any feeling and any happiness — she does not believe she deserves them as she is a “plain” woman with no fortune or connections. She suppresses her feelings and even goes so far to try and teach a young girl, Polly, how to control her emotions. The Victorians commonly believed female mental illness was “hysteria”, a side effect of having a womb and that “insanity” was caused by a lack of self-control. Brontë shows in Villette that self-control, suppression, and repression are causes of mental illness, rather than the solution.

We can see from the way Lucy describes her own mental illness (from “a terrible oppression overcame me,” to “dreadfully low-spirited.”) and the way others describe it (“he thinks you have had a nervous fever,”) that there wasn’t a language for what is clearly an anxiety disorder with depression and it wasn’t fully understood. Even Doctor John is woefully ignorant, “My art halts at the threshold of Hypochondria: she just looks in and sees a chamber of torture, but can neither say nor do much.”

However, Brontë lets the reader know her opinion on this through one of Lucy’s bold internal monologues when Doctor John says “Happiness is the cure – a cheerful mind the preventive: cultivate both” to which Lucy thinks, “No mockery in this world ever sounds to me as hollow as that of being told to cultivate happiness. What does such advice mean? Happiness is not a potato, to be planted in mould, and tilled with manure.”

Brontë is scoffing at the popular view that mental illness is a choice and that humans should control their emotions to avoid “insanity” or “melancholy”.

“I related a lot to Lucy when I read this book, which I did not expect (in fact I was very shocked when I realised that his novel was basically about a young woman’s suppressed mental health).”

I don’t want to reveal too much of the plot as I am trying to encourage you to read this fantastic book, but Lucy’s journey is both harrowing and inspiring. I related a lot to Lucy when I read this book, which I did not expect (in fact I was very shocked when I realised that his novel was basically about a young woman’s suppressed mental health). I read it after I had a nervous breakdown, caused by feeling incredibly lonely and isolated when I moved from Scotland all the way to the south of England to a small town where I struggled to make friends and connections. I ended up moving back home to Edinburgh and I am thankfully now in a better place, but I read Villette when I was recovering from the trauma. The overwhelming loneliness and hopelessness Lucy feels resonated with me, and I felt we were the same. The novel ends with her finding stable ground to live freely and honestly and I wanted the same. I think the main reason I was so inspired by this book was because it proved to me that mental health has always been a human issue, and though perhaps we experience it in different ways, it is the same story, 200 years on. Though I am not as oppressed by patriarchy as Lucy Snowe was — or at least not in the same way — the feeling of being an isolated and lonely young woman hasn’t changed.

Villette is the feminist mental health novel that we didn’t even know existed. It’s right there and waiting for us to read. Though at times the novel is dark, there are moments where Lucy Snowe’s spark inspired me and I’ll finish off this review/fangirling essay with an example.

At the start of the novel, when Lucy spontaneously leaves for Villette, she has a panic attack from the terror of making such a decision:

“All at once my position rose on me like a ghost. Anomalous; desolate, almost blank of hope, it stood. […] What prospects had I in life? What friends had I on earth? […] A dark interval of most bitter thought followed this burst…

[…]

I did not regret the step taken, nor wish to retract it. A strong, vague persuasion, that it was better to go forward than backward, and that I could go forward – that a way, however narrow and difficult, would in time open […]”

So let’s learn from the amazing Lucy Snowe. It’s always better to go forward, keep pressing and eventually you will find a way.

Josie Deacon

Josie grew up in the capital of the Highlands, Inverness, in a busy household with two older brothers, a cat, and a dog. She left school at 17 and moved to Newcastle, where she studied Drama and Scriptwriting at Northumbria University. University was the making of Josie, she got involved with a lot of film and theatre, becoming president of the Drama Society, the Scriptwriting Society, and producing, directing and acting in several short films for student film companies. After graduation Josie moved to Edinburgh with her cat, Twiggy.

When not at work, Josie loves to write, play video games and Dungeons and Dragons and also volunteers with animal welfare projects. Josie loves all animals but squirrels are her favourite.