By Rebecca Wojturska

Illustration by Ida Henrich

Content Warning: mentions of suicide attempts and disordered eating

Body Dysmorphic Disorder clouds our self-judgement. In this piece, Rebecca Wojturska documents her journey to realising what she needs to recover

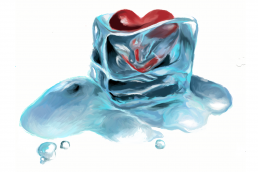

My body feels fluid. Sometimes it can feel rigid and tight. At other times both loose and round. There are even times when I can feel it growing, second by second. This isn’t necessarily dependant on what I’ve just eaten, and I don’t have some unheard-of physical disorder where my body actually changes shape (although I am a fan of shapeshifting horror). I have Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD), more commonly referred to as body dysmorphia. For anyone relatively new to the term, let me regurgitate the NHS’s definition:

“BDD […] is a mental health condition where a person spends a lot of time worrying about flaws in their appearance. These flaws are often unnoticeable to others.”

This simplistic definition doesn’t quite cut to the core of the issue, but it’s an okay start. To go back to the beginning, I was about 10 or 11 when I first started worrying about my appearance (not uncommon, sadly). Someone made a comment about the dark circles under my eyes and I convinced myself that they made me ugly. I would spend a lot of time in front of the mirror putting my fingers in front of my bags and crying at how much nicer I thought I looked. Later, I would hate how unsymmetrical my face was and spend way too much time plucking my eyebrows in an attempt to make them even (impossible). No matter what it was — my little eyes, my small lips, my too-big nose, my high forehead — I felt I was incredibly unattractive.

Not content with making me hate just my face, my BDD soon travelled south, and at the age of 12 I developed anorexia (although definitely a contributing factor, I’m not so sure BDD was a direct cause). A persistent but often well-hidden eating disorder, together with BDD, anxiety and depression, led to a 12-year self-haunting and multiple suicide attempts.

It’s important to know that BDD isn’t always coupled with anorexia and I’ve met many sufferers who never thought they looked different to how they did (whatever shape that may be), but I personally couldn’t separate the two.

It’s important to know that BDD isn’t always coupled with anorexia and I’ve met many sufferers who never thought they looked different to how they did (whatever shape that may be), but I personally couldn’t separate the two. At my very worst I would catch sight of my emaciated body reflected back at me and feel grounded with shock. Yet only seconds later I could physically see my body stretching and growing, the flesh folding and suffocating, morphing itself into something that made my heart pound painfully and left me breathless. Those were, you can imagine, horrific moments.

By the age of 18, heavy make-up, fake tan and hair extensions had become the refuge from my self-hatred (whilst simultaneously fuelling it). Of course, there is nothing intrinsically wrong with these things, but my reason for doing it was misplaced. It was a mask, a strategy to hide my ugliness in a way that the beauty industry told me was not only acceptable but attractive. But I wasn’t myself and I wasn’t happy. Constantly anxious about what other people thought about me, I believed that beauty products would help me both blend in and stand out. BDD also prevented me from leaving the house unless I thought I looked acceptable and it tore at me until my self-belief and confidence was in shreds.

It’s always tough to sum up how recovery became easier and easier. But about four years ago, I began to work harder on my mental health in a way I never did before. I started to care about myself (I realize that’s glossing over years of painful recovery but that’s for another essay.) One thing that helped sustain my recovery was meeting my partner who made me realise that my level of attractiveness is completely irrelevant to my happiness and is not the most valuable asset I can bring to a relationship. My partner also introduced me to feminism, which I’m ashamed to admit I didn’t know much about before. Feminism helped me to understand that I can love what I love, look how I look and still be a valuable person (despite what BDD tries to tell me). I still wear makeup but my reasons have changed: I have embraced what is naturally my style. Although largely recovered now, I still can’t look too long in the mirror, and I still sometimes panic about my size, which affects my mood. But I’ve found ways to cope. One way is making lists. Another way is forcing people to read them.

Ten Things I Don’t Need

- Products to tell me if I’m worth it

- Eyes that pop (whether beautifully or gorily)

- A certain-sized body

- Body shapes to be synonymous with fruit or archaic time vessels

- A symmetrical face

- Sharp cheekbones that could open a can of Irn Bru

- Mirrors pretending to reflect self-worth

- People to say “you’re not fat” (fat is more than fine: it’s necessary)

- Diet culture

- To be perfect

And the reason I don’t need these things? Because they don’t bring me that deep-seated, warm, cushioning happiness that I’ve come to value. Here’s what does:

Ten Things I Want

- Fun and adventures (without inspirational social media quotes on picturesque backgrounds)

- To accept my physical traits (note: I don’t need to love them, but to place much less importance on them is one of the most freeing feelings)

- To look how I want and not how I think I should

- To not compare myself to others

- To read. All. The. Books.

- To make people laugh and be made to laugh

- Actually, to laugh so hard that I can’t breathe and people think I’m dead but then one snort later and they know I’m okay

- To raise awareness of the massive spectrum that mental health represents

- To not wet myself in front of people whilst raising awareness of the massive spectrum that mental health represents

- To show people the same respect and compassion that I’ve received

These are things I now do and have – at least, most of the time. While my body shape will always be fluid, shifting and morphing and reforming in front of my eyes, and though my face won’t grace the covers of magazines, I will try my hardest not to waste my time evaluating myself at the mirror. My mental health will constantly fluctuate, but my determination to raise awareness about it will not.

—

NHS. 2017. Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/body-dysmorphia/. [Accessed 16 May 2018].

Rebecca Wojturska

Rebecca Wojturska works in publishing and has an academic background in literature. In 2017, she moved to Scotland for her love of the landscape, its literary world and to finally do something with her writing. Rebecca also campaigns for mental health and is an ambassador for Beat, the UK’s largest eating disorder charity. She lives in Fife with her partner and a pet-shaped hole in her heart.

Ida Henrich

Ida Henrich is a German Cartoonist, Illustrator and Designer based in Scotland. She has worked with award winning publishers, online coaches and magazines. Ida is a graduate of Communication Design at the Glasgow School of Art where she specialised in Illustration. In her own work she explores themes such sex-education, growing up, and women’s experiences. Her comics and illustrations are written for both men and women and aims to start an open dialogue between partners, friends, parents, and children about their one’s own experiences. She believes that Art is a powerful way to make ideas and feelings tangible.

As Art Editor, Ida is responsible for all things visual at Fearless Femme including the correspondence with our visual artists, the design and realisation of the online magazine and the illustration of our amazing cover girls. She will also be creating artwork for some of our articles, poems and stories.

Ida loves her coffee in the morning, that feeling after finishing an illustration and going for a run in the (Scottish) sun; and pilates on the rainy days. Ida enjoys SciFi books and autobiographies, and autobiographical comics. She is always delighted to meet new people on trains but is also smitten being home alone colouring in an illustration that she has made way to intricate while listening to Woman’s Hour. You can contact her at ida@fearlessly.co.uk.